Glomus Vagale Paraganglioma

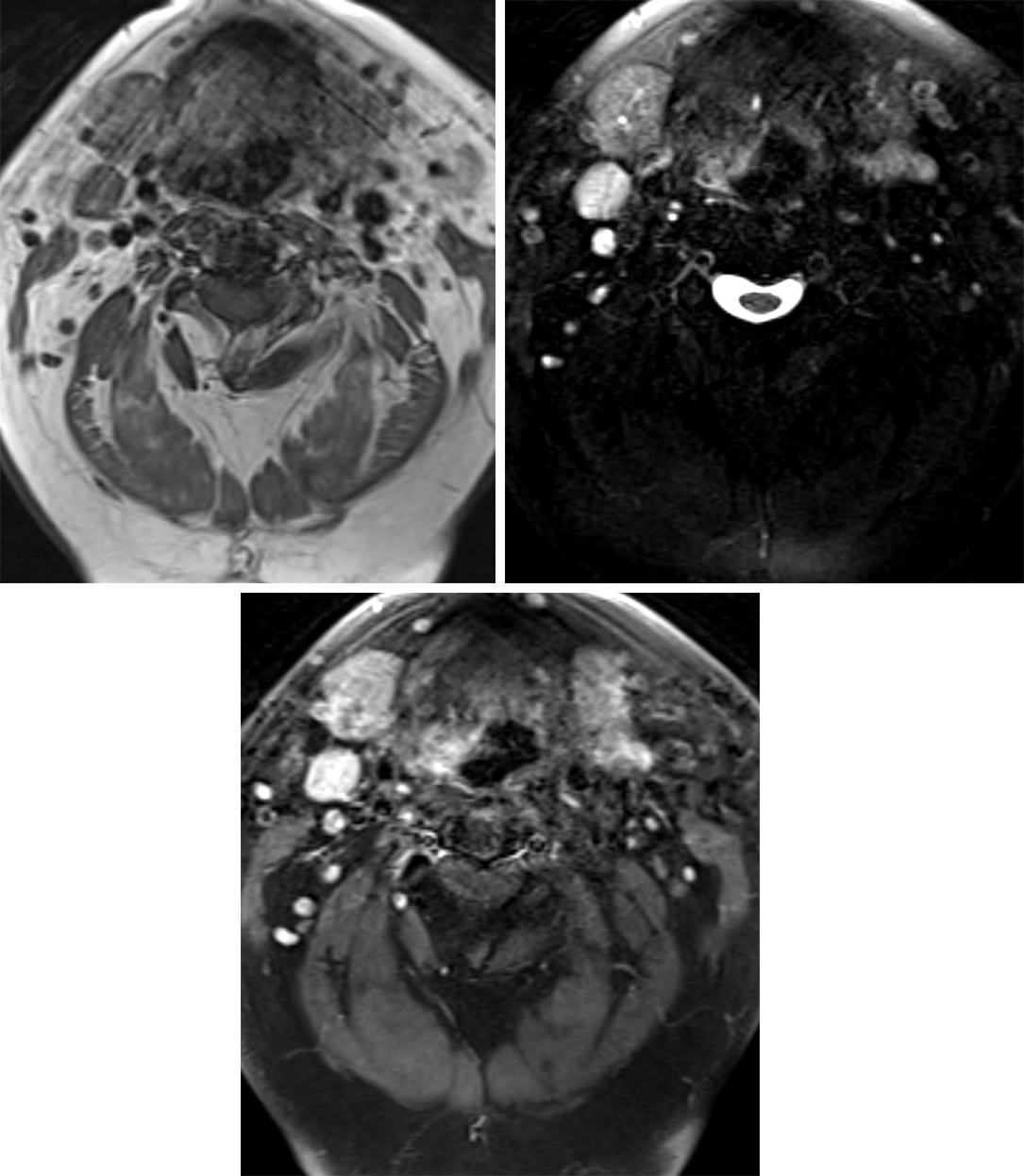

Figure 1: (Top Left) T1WI demonstrates a low-signal-intensity mass in the typical location of the vagus nerve along the carotid space. The lesion can be easily mistaken for a lymph node. As with other paragangliomas, these lesions are typically hyperintense with salt-and-pepper vascular flow voids on T2WI (top right) and avidly enhancing on postcontrast T1WI (bottom).

BASIC DESCRIPTION

- Benign, hypervascular neuroendocrine tumor of neural crest origin

- Less common than glomus caroticum (carotid body tumor) and glomus jugulare

PATHOLOGY

- Arises from glomus bodies within cranial nerve X (CN X) nodose ganglion

- Composed of chemoreceptor cells of neural crest origin

- Arterial supply from the ascending pharyngeal artery

- Familial or sporadic

- Associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1), multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN-2), and von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease, and multiple paraganglioma syndromes

- Medullary thyroid carcinoma, adrenal pheochromocytomas, multiple paragangliomas, and renal and pancreatic tumors

- Chief cells rests (zellballen) within fibromuscular stroma are characteristic microscopic features

- Neurosecretory granules on electron microscopy

CLINICAL FEATURES

- Usually afflicts middle-aged adults (40–50 years old); younger at presentation if familial

- Female gender predilection

- Common presenting signs/symptoms

- Pulsatile, painless lateral neck mass

- CNs IV to XII neuropathy (CN X most commonly); vocal cord paralysis, hoarseness

- Treatment: surgical resection versus observation; high surgical morbidity with loss of CN X function (vocal cord paralysis)

- If bilateral, only one side is resected

- Prognosis: must outweigh risks and benefits of surgery; progressive CN X neuropathy if untreated; rare malignant potential

IMAGING FEATURES

- General

- Lobulated, enhancing mass centered within the nasopharyngeal/suprahyoid carotid space ~2 cm below the jugular foramen

- Displaces the internal carotid artery anteromedially, jugular vein posterolaterally, and parapharyngeal fat anterolaterally

- No splaying of the internal carotid artery (ICA) and internal jugular vein (IJV); splaying suggests carotid body paraganglioma

- Single or multiple

- Variable size

- Right-sided position more common than left

- Hallmark “salt-and-pepper” MRI appearance

- T1WI hyperintense “salt” due to subacute hemorrhage, hypointense “pepper” due to arterial flow voids (more commonly seen in larger tumors)

- ±Adjacent permeative destruction of skull base

- CT

- Well-marginated soft-tissue mass centered within the suprahyoid carotid space ~2 cm from the jugular foramen

- Avid enhancement on contrast-enhanced CT

- ±Adjacent permeative-destructive bony changes

- MRI

- T1WI: heterogeneous signal, ±hyperintense areas of subacute hemorrhage (“salt”) is an uncommon finding, hypointense flow voids (“pepper”)

- T2WI: heterogeneously hyperintense, hypointense flow-voids

- T1WI+C: avid early enhancement

- MRA: anteromedial displacement of internal carotid artery

IMAGING RECOMMENDATIONS

- MRI without and with intravenous contrast from base of skull to carotid bifurcation; ±CT to evaluate for adjacent bony changes

- Evaluate for multiple tumors

- Imaging tumor surveillance if familial

For more information, please see the corresponding chapter in Radiopaedia.

Contributor: Rachel Seltman, MD

References

Eriksen C, Jackson CG, Miller FR, et al. Vagal paragangliomas: a report of nine cases. Am J Otolaryngol 1991;12:278–287. doi.org/10.1016/0196-0709(91)90006-2.

Mafee MF, Raofi B, Kumar A, et al. Glomus faciale, glomus jugulare, glomus tympanicum, glomus vagale, carotid body tumors, and simulating lesions. Role of MR imaging. Radiol Clin North Am 2000;38:1059–1076.

Muhm M, Polterauer P, Gstöttner W, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to carotid body tumors. Review of 24 patients. Arch Surg 1997;132:279–284. doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430270065013.

Netterville JL, Jackson CG, Miller FR, et al. Vagal paraganglioma: a review of 46 patients treated during a 20-year period. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1998;124:1133–1140. doi.org/10.1001/archotol.124.10.1133.

Olsen WL, Dillon WP, Kelly WM, et al. MR imaging of paragangliomas. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1987;148:201–204. doi.org/10.2214/ajr.148.1.201.

Osborn AG, Salzman KL, Jhaveri MD. Diagnostic Imaging (3rd ed). Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA; 2016.

Paal E. Head and neck pathology—radiology classics: vagal paraganglioma. Head Neck Pathol 2007;1:35–37. doi.org/10.1007/s12105-007-0018-1.

Rao AB, Koeller KK, Adair CF. From the archives of the AFIP. Paragangliomas of the head and neck: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. Radiographics 1999;19:1605–1632. doi.org/10.1148/radiographics.19.6.g99no251605.

Please login to post a comment.