Craniopharyngioma (Endonasal Approach)

Figure 1: Photos of a patient of Harvey Cushing who died from meningitis after surgery for a suprasellar craniopharyngioma on November 12, 1911. This image is the lantern slide that Cushing used in his lectures. The operative note by Cushing noted: “Typical interpeduncular cyst of pharyngeal origin. Sellar decompression. A badly planned operation. Death from meningitis on twelfth day.” The autopsy brain specimens on the right demonstrate the extent of tumor decompression through the transsphenoidal route.

Please note the relevant information for patients suffering from craniopharyngioma is presented in another chapter. Please click here for patient-related content.

This is a preview. Check to see if you have access to the full video. Check access

Transnasal Transtuberculum Resection of Craniopharyngioma

Craniopharyngiomas typically arise from nests of metaplastic adenohypophyseal cells of the pituitary stalk. Except for the 5% that are purely intraventricular, most of these lesions originate from the parasellar space with their nodule and extend their cystic section into the third ventricle. These tumors adhere to and encase some or all of the following structures: the optic nerves and chiasm, pituitary gland and stalk, circle of Willis, brainstem, hypothalamus, third ventricle, and the frontal/temporal lobes.

A relatively safe corridor of approach is available from below through the subchiasmatic route. These tumors and their predominantly third ventricular counterparts are most often retrochiasmatic in location; this feature makes them suitable candidates for endoscopic transnasal surgery as there is no practical transcranial route to access the retrochiasmatic space.

I have nearly abandoned the transcranial route for resection of craniopharyngiomas in favor of the transnasal route for the past few years. I believe the results of the extent of resection, patient recovery, and postoperative morbidity are in favor of the direct minimally invasive transnasal corridor. The indications for the transnasal versus transcranial approaches for this tumor type are discussed below.

Diagnosis

Although generally centered on or near the infundibulum, the clinical presentation of a craniopharyngioma depends on the tumor’s exact location relative to structures surrounding it: the pituitary gland and stalk, optic apparatus, and the third ventricle and its floor (the hypothalamus).

In adult patients, visual disturbances and headaches are the most common presenting neurologic findings. Neurocognitive changes due to infiltration of the hypothalamus are also common, although endocrine dysfunction is variable and frequently not clinically significant. In children, elevated intracranial pressure is more common, while endocrine dysfunction is usually related to growth hormone insufficiency; occult visual findings are also often present in children. Hydrocephalus occurs in one-third of both populations.

Evaluation

The primary modality to evaluate a craniopharyngioma is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This imaging modality allows characterization of the tumor, which is generally lobulated with heterogeneous signal intensity and large cysts. Computed tomography (CT) is necessary to evaluate the anatomy of the underlying skull base to assess its feasibility as an operative corridor. Additionally, the adamantinomatous subtype usually contains areas of calcification, whereas the papillary subtype, seen exclusively in adults, lacks calcification.

Given the high incidence of preoperative endocrine dysfunction with these tumors, all patients should undergo a complete endocrinologic evaluation. These tests will also facilitate management of postoperative hormone deficiency. In the perioperative setting, adrenal insufficiency and diabetes insipidus are the two potential diagnoses of primary importance and demand appropriate treatment.

Preoperative formal visual field and a dilated fundoscopic examination are required, both to document a preoperative baseline status and to provide a reference point when monitoring for future tumor recurrence. A complete understanding of any preoperative visual deficit is necessary to fully design the optimal surgical plan.

Other suprasellar lesions include a variety of pathologies that can be extrinsic (meningioma, germ cell tumor, metastasis, epidermoid cyst), intrinsic (hypothalamic or optic glioma, pituitary macroadenoma), or bony (giant cell tumor, aneurysmal bone cyst). Vascular studies (CT or MR angiography) will rule out atypical aneurysms and define the surrounding normal vasculature that may be involved in tumors extending anteriorly (anterior cerebral arteries), posteriorly (basilar apex and posterior communicating arteries), or laterally (distal internal carotid arteries and their branches). The finding of a calcified cystic mass associated with the pituitary stalk is almost pathognomonic of a craniopharyngioma.

Preoperative imaging should assess the degree of pituitary stalk involvement; this variable can potentially define the risk of its sacrifice to achieve a gross-total resection.

Figure 2: The images for two patients with craniopharyngiomas of different size and morphology are demonstrated. The images in the upper row demonstrate a large predominately solid craniopharyngioma that can be exposed via a subfrontal route through the lamina terminalis. On the other hand, the images in the middle and lower rows show typical, partially cystic and solid tumor suitable for the transnasal route. Note the nodular calcification found on CT in the right lower image. The significant involvement of both tumors with the pituitary stalk renders salvage of the stalk during resection most likely impossible.

Indications for Surgery

There is minimal evidence regarding observation for these lesions as they are almost always symptomatic at presentation. In older adults with incidental asymptomatic lesions, serial radiographic, endocrinologic, and ophthalmologic monitoring may be appropriate. However, if the diagnosis of craniopharyngioma is likely, I recommend surgery, and if the diagnosis is confirmed through frozen section, resection and adjuvant radiotherapy are instituted.

The goal of surgery is maximal safe resection. Although a surgical cure is possible with gross total resection, this should not be achieved at the cost of damaging the hypothalamus, as this leads to poor quality of life. Radiotherapy is the main adjuvant treatment, and there is an increasing role for radiosurgery or proton beam therapy to protect the surrounding vital structures.

Palliative procedures such as cyst decompression/fenestration or ventricular shunting may improve symptoms, but they generally only temporize the situation without definitively addressing the problem. Other methods of therapy such as intracavitary brachytherapy may be chosen in rare recurrent nonoperative cases.

Preoperative Considerations

Preoperative evaluation includes neuro-ophthalmologic tests with special attention to visual fields and endocrinologic testing. Neuropsychological evaluation is often helpful for lesions causing mass effect, especially those affecting the frontal or medial temporal lobes.

The majority of craniopharyngiomas (75%) have a significant suprasellar component, and the pathologic expansion of the suprasellar space defines the main operative corridor. Moreover, the extent and size of the paranasal sinuses, the involvement of surrounding vascular structures, and the expansion of the tumor lateral to the carotid arteries or into the posterior fossa determine the transcranial versus transnasal choice of approach.

Specifically, rare tumor types that are purely intraventricular may not be ideal for an endonasal approach because the intact third ventricle floor has to be preserved. Tumors that are largely solid or have a large extension lateral to the carotid bifurcation are suitable for a transcranial corridor (Figure 2). Purely intrasellar lesions, although rare, may require minimal parasellar bony exposure. Based on involvement of the hypothalamus, a preoperative plan for a gross total versus subtotal resection should be designed. Hypothalamic involvement by the tumor usually is best seen on coronal fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences.

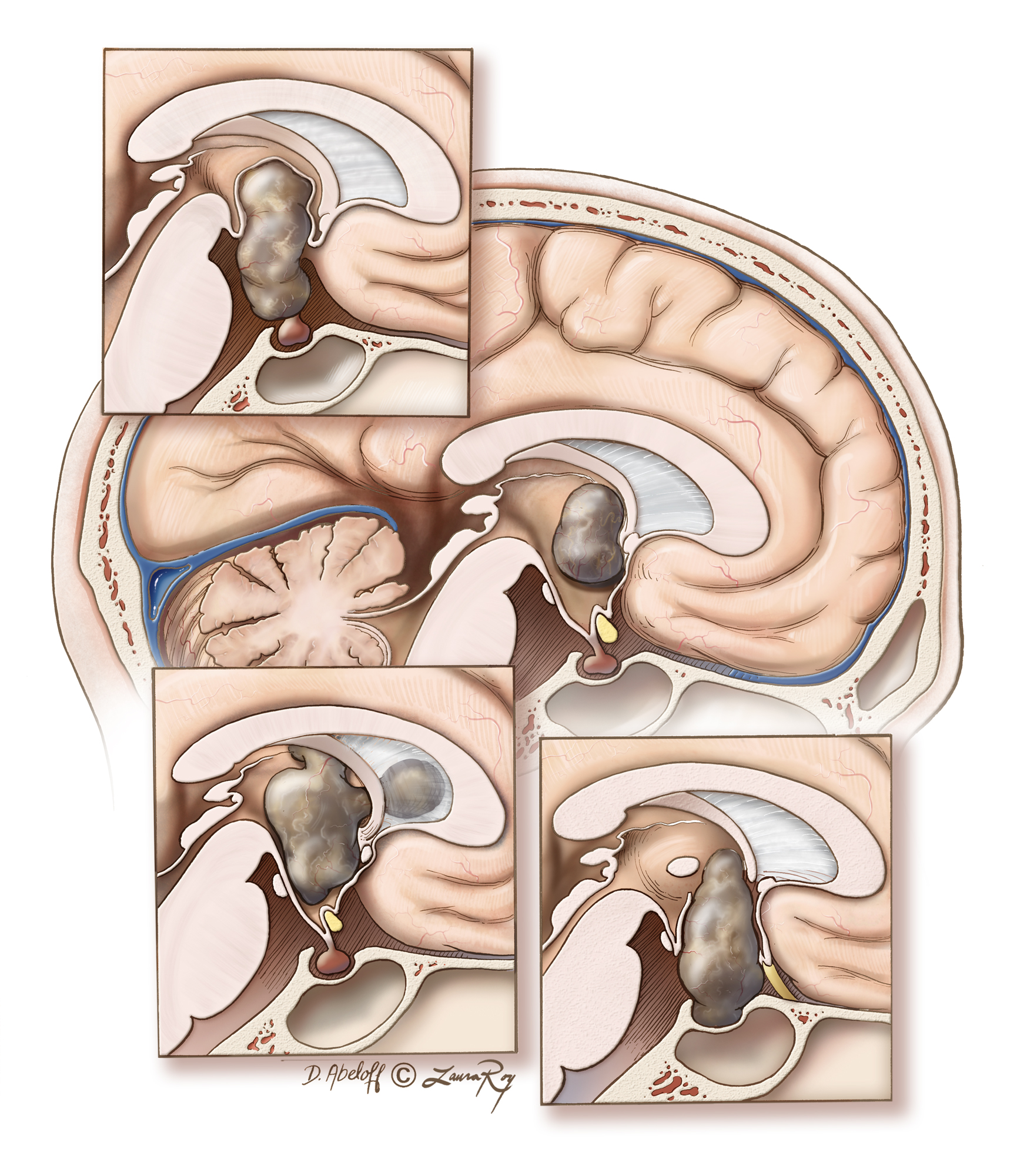

Figure 3: Craniopharyngiomas can have variable origins within the parasellar region and extend into various ventricular and cisternal spaces. The main image demonstrates the location of an intraventricular craniopharyngioma that is best approached via the transcallosal route. The top inset illustrates a typical tumor with engulfment of the pituitary stalk: I frequently reach this tumor via the endoscopic transnasal transtuberculum corridor. The left lower inset demonstrates a multicompartmental intraventricular tumor that is best resected through the transcallosal route. The last tumor configuration, right lower inset, fills the sella and lends itself to a transnasal expanded transsellar approach. The preservation of the floor of the third ventricle is an important factor during selection of the appropriate operative corridor.

ENDOSCOPIC TRANSNASAL MICROSURGICAL RESECTION OF CRANIOPHARYNGIOMAS

The technical nuances for skull base parasellar craniotomy/osteotomy are discussed in the Endoscopic Expanded Transnasal Approach chapter. Please refer to this chapter for information regarding the initial and final stages of the operation, including exposure and closure. The open transcranial approaches for resection of this tumor type are discussed in the Craniopharyngioma (Transcranial) chapter.

Figure 4: The majority of craniopharyngiomas have a large suprasellar component with cystic expansion displacing or entering the third ventricle. The sellar contents are generally displaced posteriorly, causing enlargement of the suprasellar cisterns. Shown here is the typical pathoanatomy of a retrochiasmatic craniopharyngioma.

The operative approach is through the posterior planum, mainly the tuberculum sellae and anterior wall of the sella (demarcated in blue). Note the enhanced operative working angles along the long axis of the tumor afforded by the transnasal route. Removal of the entire sellar floor is unnecessary; such bone removal would place the pituitary gland at risk and complicate skull base reconstruction at the end of resection while increasing the risk of postoperative cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage.

Figure 5: A nasoseptal flap is routinely raised. Sphenoidotomy should include a posterior ethmoidectomy to visualize the posterior planum sphenoidale, the suprasellar notch, and the full anterior wall of the sella. Mucosal removal should extend to the level of the lateral opticocarotid recesses.

A high-speed drill with a round bit is used to remove the bone of the suprasellar notch, inferiorly down the anterior wall of the sella based on the extent of the tumor, and anteriorly along the posterior planum until the anterior limit of the tumor is reached (outlined in blue, inset image). Neuronavigation provides additional guidance for the extent of the osteotomy.

If a more expanded approach is needed, the sellar floor may be removed to allow posterior displacement of the sellar contents (pituitary transposition) during tumor dissection. Lateral bony removal extends at least to the level of the medial opticocarotid recesses. If the tumor extends laterally beyond the boundaries of the sella, I attempt to remove some of the bone over the carotid arteries (top image, dotted line) to avoid blind dissection around the lateral edges of the tumor capsule.

Figure 6: When bony removal is complete, the exposed dura, including the intercavernous sinus, is cauterized with bipolar electrocautery. I use ample amount of Floseal hemostatic matrix (Baxter, Deerfield, IL) to seal the bleeding from the cavernous sinus and other venous lakes within the exposed dura. The dura is incised in a cruciate fashion.

Since most craniopharyngiomas are cystic, the extent of osteotomy and the dural opening may be smaller than the lesion itself because early cyst drainage dramatically decreases tumor size. It is mainly the nodule that needs to be microsurgically dissected. The lateral extent of osteotomy over the carotid arteries is more generous to permit dissection of the tumor nodule from the optic tracts.

The principle of judicial minimalism in bone removal, while not compromising adequate lesional exposure to conduct microsurgery, is pertinent for minimizing the most limiting complication of endonasal skull base surgery, namely postoperative CSF leakage.

Prior to dural opening, a circumferential bony edge should be mucosa-free to allow placement of the mucosal nasoseptal flap at the end of the operation, and epidural dissection for a layered closure may also be performed. Ultrasonography may be used to guide the dural opening and help the surgeon avoid injuring the carotid arteries.

INTRADURAL PROCEDURE

Upon opening the dura, preinfundibular tumors are immediately visible. There is often a thin layer of arachnoid covering the tumor that should be opened sharply. It is important to identify the stalk and the superior hypophyseal arteries as early as possible during surgery to facilitate their preservation for as long as possible until it is determined that gross total resection necessitates the sacrifice of the pituitary function.

Figure 7: Upon opening the dura, the tumor capsule may be the only visible structure and it may be thickened and opaque. The operator should remain patient and decompress the tumor and its associated cyst, because this maneuver will mobilize the mass and allow identification of the surrounding cerebrovascular structures, including the optic chiasm.

Figure 8: After the initial debulking and cyst drainage, extracapsular dissection is initiated anterior to the capsule within the subchiasmatic space. Sharp dissection avoids avulsion of the fine vasculature, and protects the branches of the superior hypophyseal arteries supplying the chiasm, pituitary stalk, and posterior optic nerves. The intraoperative photo (right image) demonstrates the solid tumor nodule posterior to the chiasm elevated by the suction apparatus.

Figure 9: Once the anterior tumor is no longer tethered to the chiasm whose location is reliably identified, the capsule may be safely manipulated further and opened more widely (inset image). More aggressive internal debulking is now safe and possible; ring curettes are used to remove the solid or calcified portions. Further cyst aspiration deflates the tumor.

Figure 10: The lateral tumor capsule is now dissected by entering the opticocarotid cistern using angled dissectors and a 30-degree endoscope. By gently medializing the tumor capsule, I stretch and sharply cut the arachnoid adhesions and membranes. The operator traces the medial border of the internal carotid artery superiorly, while taking care to identify and preserve the superior hypophyseal arteries; tumor-feeding arteries are coagulated and cut and en passage vessels are strictly protected. This is repeated contralaterally to free both lateral tumor margins.

One of the most common reasons for visual deterioration after surgery is indiscriminate sacrifice of the subchiasmatic perforating arteries entangled in the arachnoid membranes and tumor capsule.

Figure 11: Sharp tumor capsule dissection continues along the superior and lateral arachnoid planes in a stepwise fashion to fully release the rest of the chiasm. These tumors frequently infiltrate and expand posteriorly behind the optic chiasm into the hypothalamus, resulting in a defect at the floor of the third ventricle. Through this defect, the tumor grows its intraventricular component.

The posterior dissection plane should disconnect only the portion of the hypothalamus that is clearly dominated by the tumor; any partly normal-appearing tissue along the floor of the ventricle should be spared. The tumor-hypothalamus border may not be clearly apparent.

Figure 12: Once the optic apparatus is free, the capsule of the cystic portion of the tumor is dissected from the walls of the third ventricle. Although gentle traction may be necessary to identify the planes, forceful impatient pull on the tumor capsule can cause hypothalamic injury and should be avoided. An 45-degree angled endoscope allows inspection of the third ventricle and hypothalamus (inset image). Tumor fragments may be left adherent to the walls of the ventricle or hypothalamus to avoid injury to these vital structures. The rest of the capsule may now be dissected posteriorly.

Figure 13: Next, the inferior tumor capsule is sharply dissected from the compressed sellar contents. If an intrasellar component is present, the diaphragma sella must be incised. The pituitary stalk is inspected for disease involvement and preserved, if possible, to minimize postoperative hormonal morbidity (inset images: upper configuration precludes preservation of the stalk and the lower inset image illustrates a reasonable plane between the tumor and stalk). Based on the surgeon’s judgment, the stalk may be sacrificed to achieve gross total resection, especially if the patient is suffering from pituitary dysfunction before surgery.

Figure 14: Following management of the pituitary stalk, the tumor is often still tethered posteriorly to the mammillary bodies or basilar artery and its branches. It is important to resist the temptation to pull on the tumor at this stage. The tumor should be sharply and patiently dissected from the mammillary bodies, optic tracts, membrane of Liliequist, posterior cerebral arteries, posterior communicating arteries, and the thalamoperforators. An angled endoscope allows microsurgery under direct visualization.

Figure 15: Using bimanual microsurgical techniques, the tumor is sharply dissected from the pituitary stalk using angled microscissors. This disconnection often releases the capsule and allows its delivery.

Figure 16: The tumor capsule is now circumferentially free and is removed. The tumor cavity and third ventricle are inspected with straight and angled endoscopes for bleeding and residual tumor. Note the view into the third ventricle, around the basilar bifurcation and posterior cerebral arteries (top inset and lower images). If residual intraventricular tumor is present, it may now be re-evaluated for further safe resection. Copious irrigation with warm normal saline is used to avoid chemical meningitis from residual cyst contents and to achieve hemostasis.

Case Example

This patient presented with visual decline and was diagnosed with a suprasellar craniopharyngioma of moderate size.

Figure 17: MR imaging demonstrates the moderate size, mostly solid craniopharyngioma. Note the limited transsellar-transtuberculum osteotomy necessary for resection of this tumor; Only the tumor capsule was apparent upon dural opening (second row, left image). Upon decompression of the tumor mass, the pituitary stalk was readily dissected from the tumor capsule (second row, right image). The tumor capsule was also dissected from the ICA and superior hypophyseal artery (red arrow)(third row) as well as the undersurface of the chiasm (fourth row). The contralateral optic radiation was also released and the tumor removed; the integrity of the pituitary stalk was confirmed (last row).

Craniopharyngioma: Endoscopic Transtuberculum Approach

Closure

Meticulous closure is necessary to avoid postoperative CSF leakage that can spoil a good resection result.

Figure 18: Once tumor resection is complete, a gasket closure technique is conducted by first placing an oversized dural substitute or facial graft, followed by a countersunk rigid implant. Depending on the lateral extent of the bony opening, notches are cut into the implant to avoid contact with and compression on the optic nerves. Alternatively, a layered closure using harvested or allograft dural reconstruction materials may be conducted. Valsalva maneuvers are used to allow the surgeon to detect any obvious CSF fistulas.

The nasoseptal pedicled mucosal flap that was harvested at the beginning of surgery is then placed over the seal and covered with fibrin glue. See the Endoscopic Expanded Transnasal Approach chapter for more details on closure.

Postoperative Considerations

The patient is observed in the intensive care unit overnight for frequent neurologic evaluations and pain and blood pressure control. Entry into the ventricular system carries a higher risk of postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leak. Therefore, lumbar drainage is used for 3-4 days after surgery; the patient is then mobilized.

The best timing for the initiation of lumbar drainage is controversial. Some operators delay drainage for 4-6 hours after surgery while others start drainage immediately. I wait for the CT scan on the first postoperative day to exclude significant pneumocephalus that can worsen with CSF drainage. Stress dose steroids are continued postoperatively until endocrinologic status can be assessed in detail.

A postoperative MRI is obtained to assess the extent of resection and plan for delayed radiotherapy. I do not use prophylactic anticonvulsants unless cortical disruption was noted intraoperatively. Standard precautions to the patient are recommended; including avoidance of nose-blowing, using a straw to drink, and unnecessary bearing down.

Diabetes insipidus (DI) is one of the more frequent postoperative complications after transsphenoidal surgery, which can exists preoperatively and worsens postoperatively. The etiology of DI relates to distention or injury of the neurohypophysis or pituitary stalk. Careful monitoring of fluid input/output, urinary osmolality and frequent serum sodium evaluations are imperative during the immediate postoperative period as serum sodium may rapidly escalate to dangerous levels (>145mEq/L).

Routine early postoperative diuresis related to frequent intraoperative fluid boluses must be distinguished from DI. This can be achieved with a water deprivation test: early postoperative diuresis will not impact plasma osmolality or sodium. The water deprivation test involves withholding water intake for 6-8 hours and checking urine osmolality, which in the setting of DI fails to exceed 200mOsm/kg due to the patient’s inability to concentrate his or her urine. This will correspond to a rise in plasma osmolality, such that it can near 320 to 330 mOsm/kg.

Treatment for DI depends on the patient’s functional status; a conscious patient with intact natural thirst mechanism can maintain plasma osmolality. The patients with severe DI or those who are unconscious can be managed with desmopressin (DDAVP).

Approximately 60% of patients can experience transient DI postoperatively, with less than 10% continuing on to permanent DI. Dysregulation of the anterior pituitary hormones is also common.

Hyperphagia leading to morbid obesity is a well-described complication following craniopharyngioma resection that is caused by hypothalamic injury, especially in children.

Pearls and Pitfalls

- Early central decompression creates room for subsequent extracapsular tumor dissection, especially of cystic components.

- Sharp and gentle dissection of the arachnoid planes is critical to avoid injuring the fine superior hypophyseal branches that supply the optic chiasm.

- Angled endoscopes allow thorough inspection and further resection of residual tumors in the difficult-to-reach locations under direct vision.

- A small part of the floor of the ventricle may be predominantly involved with the tumor and should be considered part of the tumor capsule. However, most of the hypothalamus and other adjacent neural areas must be preserved. If necessary, a small piece of adherent residual capsule may be left behind on the walls or floor of the third ventricle.

Contributor: Charles Kulwin, MD

References

Conger AR, Lucas J, Zada G, Schwartz TH, Cohen-Gadol AA. Endoscopic extended transphenoidal resection of craniopharyngiomas: nuances of neurosurgical technique. Neurosurgical Focus. 37:E10, 2014.

Please login to post a comment.