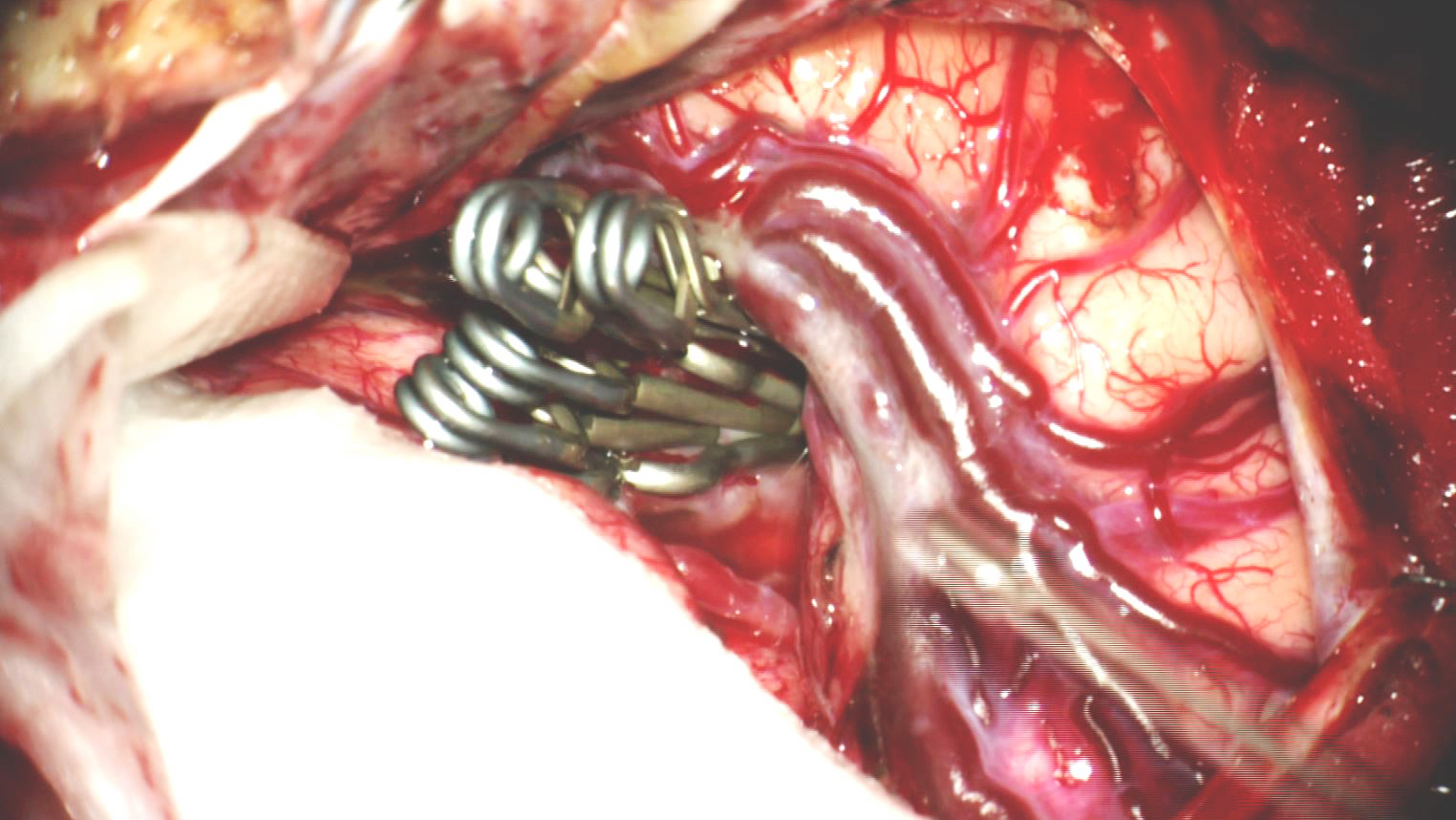

Permanent Clip Application

Figure 1: Clip ligation of a giant atherosclerotic right-sided MCA aneurysm is shown. The following chapter will review the nuances of technique for such maneuvers.

Clip Selection

The selection of a specific style and shape of the aneurysm clip is made before the surgery based on the aneurysm’s anatomy including its size, shape, location, and morphology of the parent vessels and surrounding structures.

The surrounding neurovascular structures, including the cranial nerves, affect the candidacy of a clip. Depending on the aneurysm, different clip styles and clipping techniques may be required for complete occlusion and collapse of the aneurysm neck. Select aneurysms require multiple clip or specialized clip configurations based on a careful study of the preoperative angiography.

My philosophy for clip selection revolves around these principles:

- The clip blades should preferably be applied parallel to the long axis of the parent vessel to avoid an “accordion effect” along the parent vessel’s lumen, which could lead to partial closure of the blades.

Clip Deployment Parallel to the Long Axis of the Parent Artery during Ligation of an Atherosclerotic PCoA Aneurysm

- The simplest clip configurations (straight, curved, or angled clips) are often most effective. Straight and angled fenestrated clips are my second most favorite clip configurations.

- The shortest clip blade is the safest. Excessively long clips own lower closing pressures at the end of their blades and can inadvertently injure perforators.

- Single rather than multiple clip applications are preferred, when possible.

Obtaining Optimal Visualization

After the dissection of the subarachnoid space, proximal vascular control and proper exposure of the aneurysm, the surgeon focuses on the optimal unveiling and clip ligation of the aneurysm neck. I have a low threshold for temporary clip ligation of the proximal parent artery to partially deflate the sac and manipulate the neck and part of the dome to thoroughly expose the neck and understand its morphology in relation of the branching and perforating arteries.

Premature permanent clip application without a clear understanding of the neck anatomy is one of the most common causes of suboptimal clip deployment and intraoperative rupture among novice surgeons. I insist on a thorough circumdissection of the neck so the blades are gliding around the neck effortlessly. The clip blades often obstruct the view of the surgeon during clip deployment; therefore, the blades should not be used to complete the dissection or blindly penetrate operative blind spots.

Premature Intraoperative Rupture of a Small ACoA Aneurysm due to Inadequate Neck Dissection

Depending on the aneurysm location and projection of the dome, neck inspection and mobilization may be imperative because the aneurysm may block proper visualization of specific vasculature. For example, an inferiorly projecting saccular anterior communicating artery (ACoA) aneurysm may obscure the surgeon’s view of the contralateral A1 segment, preventing a complete proximal control on both A1 branches. In these cases, the surgeon must feel comfortable clipping the aneurysm without complete proximal control while also maintaining a plan for quick resolution in the event of premature aneurysm rupture. This plan may include placement of a tentative permanent clip to gather the aneurysm sac, allowing for more room to find the contralateral A1.

After proximal control is secured, the aneurysm neck should be dissected and the dome avoided if possible, providing the necessary terrain for proper clip deployment. During this final dissection stage, all relevant vasculature, must be accounted for and gently mobilized. Small perforating arteries are often the most difficult to spare and the most troublesome because their occlusion will cause long-term neurologic sequelae.

It is essential that sufficient operating space be procured during dissection to allow complete visualization along the entire path of the clip blades. The aneurysm neck, afferent and efferent vasculature, and the clip blades should be visualized throughout the passageway of the blades. Using the tip of the blades for blind dissection during final clip implantation has calamitous consequences and leads to tears near the aneurysm neck and dome.

Unfortunately, the fine details of aneurysm surgery, including aneurysm projections and minimization of brain retraction, leave little room for maneuverability of the clip appliers. As such, the surgeon should secure flexible viewing and working angles through a wise choice of clip configurations and arachnoidal dissection while minimizing parenchymal retraction.

If the commanding view of the aneurysm is lost by the bulk of the clip appliers or other surgical tools within the operative field, the microscope should be repositioned to facilitate proper viewing or additional atraumatic dissection should be performed. Use of the mouthswitch is critical for allowing the surgeon to keep the image in focus during fine adjustments in clip position while the neck is manipulated. Bimanual dissection and handling of the neck is the key founding principle in reaching a desirable clip construct.

Aneurysm Clip Application

The location and underlying pathophysiology of an aneurysm dictate how the aneurysm should be clip ligated. The pathophysiology of aneurysmal anatomy has been well described by Rhoton’s four rules of saccular aneurysms:

First, aneurysms often arise at the branch point of an efferent artery emerging from a parent artery. Such aneurysms may also occur at bifurcations where a parent artery splits into two distinct efferent arteries.

Second, saccular aneurysms arise in curved segments of arteries due to the inertia of the blood flow. More specifically, the aneurysm tends to arise on the convex portion of the curvature.

Third, the dome of the aneurysm will project in the preferred direction of blood flow, the direction the blood would have travelled if the curve had not been present.

Fourth and finally, perforating arteries that must be protected during a clipping procedure surround almost all aneurysms.

The clip should not only serve to stop blood entering the aneurysm, but also prevent future aneurysm formation at the point of clip application. Aneurysms that occur at bifurcations or branch points should be clipped perpendicular to the afferent vessel. Aneurysms that occur in the curvature of a vessel should be clipped parallel to their parent vessel. Although these rules provide general guidelines for clip ligation, it is almost impossible to adhere to them routinely; the surgeon must maintain a flexible operative plan and deploy the clip with a number of anatomical constraints in mind, including the available working angles and adjacent perforating vessels.

The final decision regarding the choice of the clip should be based on a thorough understanding of the aneurysm’s anatomy. This understanding should not be complicated or rushed because the surgeon is uncomfortable starring at a pulsating aneurysm. Moreover, clip application should not proceed without clear visualization of the neck under high magnification.

Simple (Straight, Curved, and Angled) Clip Ligation Techniques

Clipping an aneurysm with a simple clip involves placing a straight, curved or angled clip blade onto an aneurysm neck to collapse the neck and occlude blood flow. This clipping strategy is preferred for smaller aneurysms with simple and well-defined narrow necks. Before clip placement, the surgeon must ensure that the clip blades are long enough to span the entire neck.

Longer straight-blade clips may occasionally be used if the surgeon is attempting to clip ligate deep-seated aneurysms when the clip appliers block his or her view during clip deployment and the adjacent vasculature and cranial nerves provide limited working space. This often occurs during surgery for basilar bifurcation or posterior inferior cerebellar artery aneurysms.

Figure 2: Simple clipping of middle cerebral artery (MCA) aneurysms is demonstrated. The small saccular aneurysm appears on the convexity of the right efferent branch of the MCA. The blades are placed parallel to the parent vessel (left image). The aneurysm frequently arises at the bifurcation, and the clip is placed perpendicular to the afferent artery (right image). “Perfect” clipping may have disadvantages, especially for atherosclerotic aneurysms, because external inspection may not detect the luminal compromise caused by the collapse of the thick walls of the afferent and efferent vessels.

Figure 3: Simple clipping of a small posterior communicating artery (PCoA) aneurysm using a straight clip is shown. This aneurysm is mainly an internal carotid artery (ICA) aneurysm, rather than a PCoA aneurysm. Application of the clip may compromise visualization of the PCoA. This consideration is important during deployment of the clip to ensure that the PCoA is not compromised.

Figure 4: An anteriorly projecting ACoA aneurysm is clipped via a simple straight clip (left image,) this is a common clipping method for such aneurysms. A superiorly projecting ACoA aneurysm is clipped using a single angled clip (right image) along the coronal plane. Although this clip application is not ideal, anatomical constraints may not provide more flexible options. The ACoA perforators must be protected. Regardless of the clipping method, the origin of the contralateral A2 segment is usually obscured by the aneurysm.

Figure 5: Three different, simple clipping techniques for superior cerebellar artery aneurysms are illustrated. The aneurysm neck is clipped using a single angled clip, parallel to the afferent artery (basilar artery) from which the aneurysm arises, and perpendicular to the efferent branch (left upper image); the aneurysm is more on the afferent rather than efferent vessel. The aneurysm may also be clip ligated using a curved clip (right upper image). The curved blade allows a better exclusion of the aneurysm base. If the basilar bifurcation is “high,” an angled clip may be applicable (lower image). In the lower image, the aneurysm originates equally from both the basilar and superior cerebellar arteries.

Figure 6: A pericallosal artery aneurysm is clipped with an angled clip. The aneurysm arises at the point of bifurcation and the clip is placed perpendicular to the afferent pericallosal artery.

Figure 7: An ophthalmic artery aneurysm is shown clipped with an angled clip. The aneurysm neck comes off of the origin at the efferent branch, and is clipped parallel to both the efferent and afferent arteries.

Figure 8: An internal carotid artery (ICA) bifurcation aneurysm is shown clipped using a simple straight clip (left image) or an angled clip (right image). The angled clip may avoid the MCA branch, ensuring that the hinge of the clip does not kink its lumen. The medial ICA perforators must be saved.

Figure 9: A medially-projecting ICA bifurcation aneurysm may be clipped with a curved clip. The curved clip nicely contours the bifurcation, allowing easy visualization during its passage and limited interaction with the perforating vessels.

Figure 10: Simple bayonetted clips provide flexibility in their application while preventing the bulk of the clip applier from obstructing the surgeon’s view. In this case, an anterior choroidal artery aneurysm was clipped through a small working space while the artery was in view during clip deployment (left image). Angled fenestrated clips accomplish the same task for posteriorly pointing aneurysms (right image).

Fenestrated Clip Ligation Techniques

Fenestrated clips are abundantly useful and have expanded the safety of clip ligation for more complicated aneurysms. Fenestrated clips are designed so that there is a circular opening at the heel of the clip blades through which the parent or perforating arteries may be safely housed. As is the case with simple clips, fenestrated clips are produced in a number of conformations, including angled forms. Importantly, fenestrated clips work well in conjunction with other aneurysm clips when multiple clips are required for effective exclusion of the neck and reconstruction of the lumen of the parent vessel.

The three primary indications for deployment of fenestrated clips are:

- To avoid an afferent or efferent artery, including perforating vessels

- Tandem clipping to close the distal neck of the aneurysm not handled by the first clip

- Reconstruction of the lumen of the parent vessel.

Figure 11: An anterior cerebral artery (ACA) A1 segment saccular aneurysm is excluded via an angled fenestrated clip (left image). The fenestration encircles the A1 segment without its compromise. Clip ligation via two fenestrated angled clips, facing each other, allows more flexible maneuvering of the blades around the wider base aneurysm while avoiding the perforating vessels on the medial side of the parent vessel.

Figure 12: An anteriorly or superiorly-projecting ACoA aneurysm is ideally clipped using a straight fenestrated clip. The fenestration encircles the ipsilateral A2 segment. The clip must be carefully positioned to avoid occluding the recurrent artery of Heubner or the contralateral A2 origin.

Figure 13: Another view of clip application for ACoA aneurysms is illustrated. Most ACoA aneurysms originate from the junction of the ACoA and A2 on the side of the dominant A1. The clip must be slightly angled anteriorly in the axial plane to cover the stretch of the aneurysm neck on the A2 and ACoA (left image). If the aneurysm neck is entirely based on the ACoA (rare,) both A1s are usually dominant and the clip application is more straightforward, parallel to the ACoA (right image).

Figure 14: Bulbous and broad-necked aneurysms present a challenge. The operative blind spot along the medial wall of the ipsilateral A2 may lead to improper clip positioning and residual aneurysm filling (left image, upper inset). The clip must be angled to close the neck on the ipsilateral A2 (left image, lower inset). Larger and atherosclerotic aneurysms require more than one clip for complete neck closure (right image).

Figure 15: A large PCoA aneurysm is managed via an angled fenestrated clip (top image). Large or posteriorly-pointing PCoA aneurysms arise adjacent to the branch point of the ICA into the PCoA. A similar technique is illustrated for an anterior choroidal aneurysm (bottom image). The fenestrated clip encircles the ICA and reconstructs its lumen parallel to the long axis of the ICA. Compared to a perpendicular clipping method, this configuration fully occludes the aneurysm neck with minimal risk of delayed clip slippage or incomplete blade closure. I favor this clipping strategy for large PCoA aneurysms. Additionally, this mode of clip placement does not necessitate significant manipulation of the anterior choroidal artery adherent to the dome.

Figure 16: A posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) aneurysm is occluded with a fenestrated clip. The fenestrated portion of the clip encloses the PICA. Often a slightly imperfect clip deployment is necessary to preserve the small lumen of the PICA and save the distal vertebral artery.

Figure 17: A medially projecting broad-based ICA bifurcation aneurysm is occluded via a right-angled fenestrated clip. The fenestration encases the MCA. The medial perforating vessels should be preserved.

Figure 18: A vertebral artery aneurysm is situated at the branching point of the efferent anterior spinal artery. The fenestrated portion of the clip encircles the small-caliber anterior spinal artery.

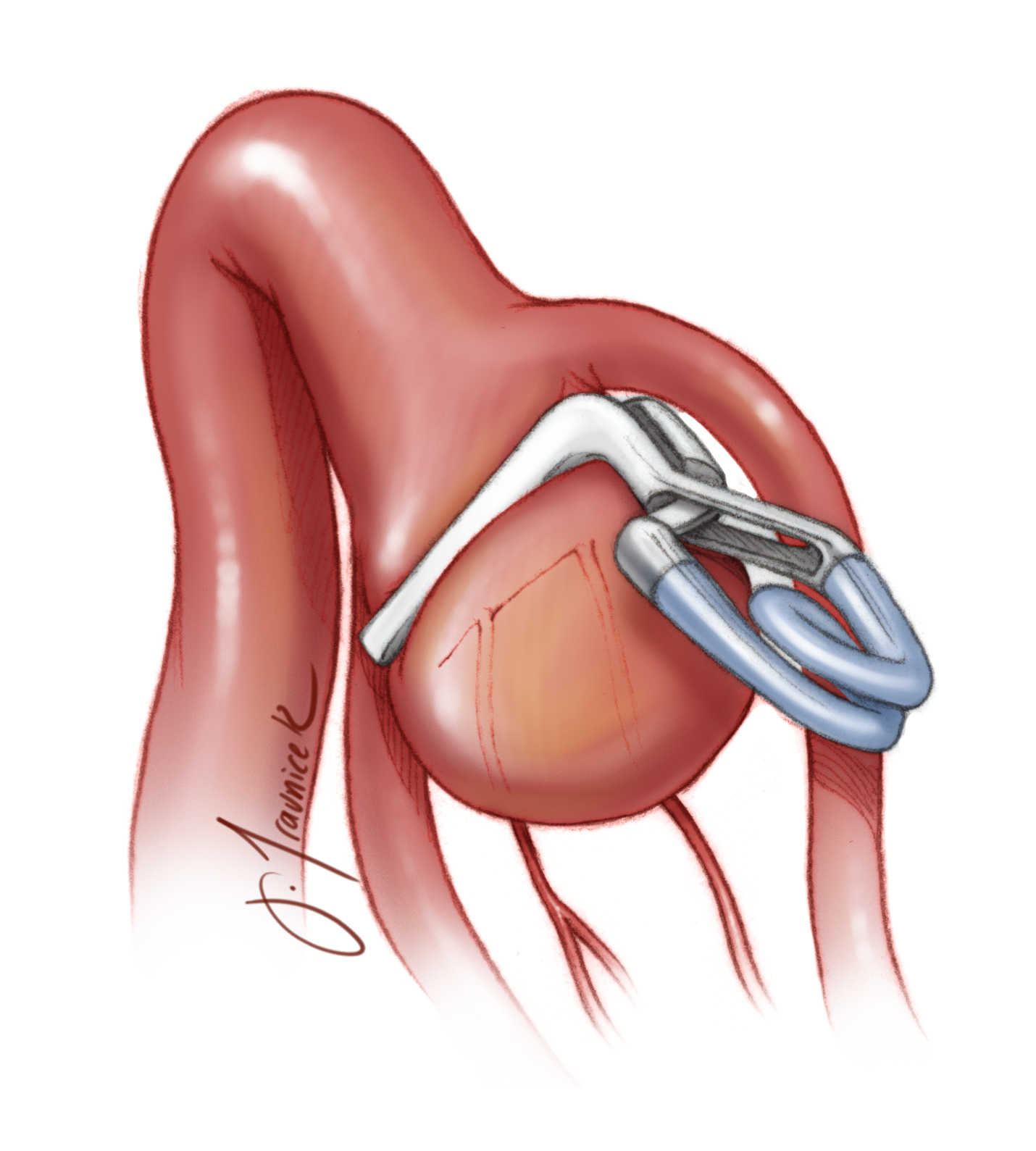

Multiple Clipping Strategies

Although I generally prefer to use the simplest and fewest number of aneurysm clips when possible, a single clip often will not fully occlude a large atherosclerotic aneurysm neck. Endovascular techniques have significantly raised the bar of complexity for microsurgery on these aneurysms. The most inaccessible portion of the neck requiring difficult working angles should be clipped first. Overall, multiple-clip strategies allow more flexible reconstruction of regional vasculatures’ lumens while effectively excluding the aneurysm neck.

Multiple clips may be used to fully collapse an aneurysm neck by overstacking, stacking from the aneurysm neck toward the aneurysm dome, or understacking, stacking from the distal portion of an aneurysm dome or neck down toward the parent artery. In both scenarios, the subsequent clip blades are applied parallel to the previous clip.

Booster clipping techniques are devised to reinforce a previously placed clip. The booster clip may be applied perpendicular to the previous aneurysm clip or parallel. In rare cases, the booster clip is applied so that its blades encompass the blades of the previously applied clip, ensuring its tight closure.

Tandem clipping is a method of clip ligation where the aneurysm neck is first clipped proximally using a single fenestrated clip. Unlike simple clips, the fenestrated clips present most of their closing pressure at the end of their blades. Additional clips are then stacked proximal or distal to the first clip, effectively occluding the neck by closing it at the area of the fenestration. Tandem clipping is especially useful with atherosclerotic, broad-based and giant aneurysms.

In the case of an atheroma, the first fenestrated clip should be placed with the fenestrated portion over the atheroma, thereby occluding the distal neck and avoiding the incompressible atheroma that would necessarily prevent the blades from closing. Next, a second clip is placed just distal to the atheroma, thereby completely occluding the aneurysm neck without the need for an endarterectomy.

Long clips have a reduced closing pressure at the end of their blades and should be avoided for broad-based aneurysms.

Tentative clipping pertains to placement of an initial clip to gather or deflate the large dome and allow more visualization around the neck. This clip is then repositioned or replaced after the neck morphology is better understood.

These concepts are illustrated below.

Figure 19: Fenestrated clipping followed by booster clipping of an anteriorly-projecting ACoA aneurysm with a neck that extends into the A2 segment is demonstrated. The primary clip is applied in the proximal position. The second clip is applied distal to the first clip to ensure complete closure of the aneurysm neck.

Figure 20: Clipping of an ACoA aneurysm after a prior partial coiling attempt. Short fenestrated clips are stacked to trap the coiled material in a lateral section of the aneurysm and a longer distal clip occludes the entire dome. These clips are placed in order from 1 to 4 using an understacking method (left image). Three longer fenestrated clips are used to occlude the entire aneurysm using an overstacking method (right image). The coiled material is pinched between the clip blades.

Figure 21: A large PCoA aneurysm with a wide neck is clipped via two right-angled fenestrated clips. These two clips are placed in tandem formation in order to fully collapse the aneurysm neck. The anterior choroidal artery is shown just distal to the left clip. The PCoA can be seen traversing around the inferior pole of the aneurysm. This construct is favorable at it reconstructs the lumen of the parent vessel effectively and places the anterior choroidal artery at least risk.

Figure 22: Tandem overstacked clipping of a basilar artery bifurcation aneurysm is evident. The proximal tentative fenestrated clip is placed first, occluding the distal portion of the aneurysm neck and improving visualization of the aneurysmal anatomy. The second straight clip is placed just distal to the fenestrated one, occluding the remaining portion of the aneurysm neck.

Figure 23: Tandem understacked clipping of a basilar artery bifurcation aneurysm is very beneficial. The fenestrated clip is placed distally on the aneurysm, closing off the most distal portion of the neck. The second simple clip is deployed just proximal to the fenestrated one, collapsing the remaining portion of the neck. The efferent arteries are readily spared while appropriate neck exclusion is rendered.

Figure 24: A tandem overstacking technique for ligation of a basilar artery bifurcation aneurysm with thick walls is illustrated. An additional booster clip is also applied. The proximal fenestrated clip was placed first, occluding the distal portion of the aneurysm neck and improving visualization of the aneurysmal anatomy. The second simple clip was then placed just distal to the fenestrated one, occluding the remaining portion of the neck. Intraoperative fluorescence angiography demonstrated persistent filling of the aneurysm. Next, a booster clip was positioned just distal to the straight clip, ensuring that the aneurysm is completely closed off.

Vessel Reconstruction Methods

Unfortunately, some aneurysms do not stem from one afferent or efferent artery, but instead have an aneurysmal neck that seemingly arises from or incorporates both. If careful dissection does not disclose a relatively defined clippable neck, the occlusion of the aneurysm often requires reconstruction of the parent vessels to provide either anterograde or retrograde flow.

Vessel reconstruction may be performed with simple or fenestrated clips at any necessary angle. Anterograde vessel reconstruction will create a lumen that passes blood to an efferent artery. In an anterograde reconstruction, the blood will follow a natural path and does not need to be rerouted. A retrograde vessel reconstruction will reorient the blood flow before it enters into an efferent artery.

Aneurysms that occur at bifurcations may require dome reconstruction. Simply clipping the aneurysm with a single clip, multiple clips, or tandem clips at the base may occlude or stenose the efferent arteries. In this situation, the dome reconstruction technique involves deployment of a collection of simple and/or fenestrated clips on the aneurysm dome; the feet of the clips leave enough room at the base of the aneurysm for continued flow into the efferent arteries.

Figure 25: A basilar artery aneurysm is clipped with a tandem overstacking method to allow retrograde flow into the efferent P1 segment of the posterior cerebral artery. The blood flow is indicated with the green arrows. The aneurysm is first clipped using a fenestrated clip on its proximal neck. A second fenestrated clip is placed just distal to the first one, creating a lumen for blood flow. Finally, a simple clip is placed just distal to the second fenestrated clip, rerouting the flow into the efferent P1 segment rather than the dome.

Figure 26: A dome tube vessel reconstruction technique with stacked fenestrated clips is illustrated. The dome is clipped from its most distal point to its most proximal. Blood flow is unimpeded at the proximal neck of the aneurysm. Imperfect clipping is important to avoid even subtle flow changes that can lead to ischemia in the distal MCA territories.

Clip Reconstruction Techniques

I occasionally need to incise the aneurysm in order to facilitate clip ligation at the aneurysm neck. This situation arises if 1) the aneurysm is excessively large, 2) there is an atheroma or thrombus at the neck that does not allow blade closure, or 3) a coil must be removed after a failed coiling attempt.

Before incising the aneurysm, a complete proximal and distal vascular control over the involved branching arteries is obviously mandatory. This complete regional circulatory arrest (versus only proximal occlusion) is accompanied by time constraints; the time-dependent risk of ischemia is highly contingent on the patient’s collateral circulation and hemodynamic status. Thus, the surgeon must have a clear plan before aneurysm opening that will permit expedient dissection, clipping, and subsequent reperfusion.

Unfortunately, there is no reliable method to evaluate the support of the collateral circulation and risk of ischemia. Younger patients tend to tolerate regional circulatory arrest much more readily than older patients with atherosclerosis.

I incise the wall of the aneurysm over the thrombotic region of the sac and continue evacuation of the thrombus until bleeding from the live part of the sac is encountered; only then I apply the clips so that the period of temporary occlusion is minimized. After removal of the impeding intrasaccular material, the aneurysm neck must be reconstructed to create suitable lumens for the parent vessels. The reconstruction may be performed through suturing, stacked straight or curved clips. Immediately upon neck reconstruction, the flow should be restored. It is important to keep the blades way from the diseased inlets and outlets of the involved vessels, as perfect clipping will easily lead to their collapse.

Figure 27: Neck reconstruction for a large MCA bifurcation aneurysm is demonstrated. The aneurysm neck may rarely be reconstructed by a simple suturing technique (upper image). The aneurysm may also be excluded via a series of stacked straight clips (left lower image) or closely approximated with angled clips (right lower image).

Inspection after Clip Ligation

Once a permanent clip has been successfully deployed, the surgeon must diligently inspect the aneurysm for continued filling, the efferent, afferent, and perforating vasculature for patency, and the surgical blind spots.

Special care should be given to the inspection of the perforating arteries as they are likely to be trapped between the blades and overlooked during the operation. I use a blunt dissector to gently press against the dome of the aneurysm; persistent filling will pulsate the tip of the dissector.

At this time, the surgeon may also choose to take advantage of any neurological monitoring and intraoperative angiography tools that are available. The relevant tools include, but are not limited to, microdoppler ultrasonography, somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEPs,) motor evoked potentials (MEPs,) and indocyanine green versus fluorescein videoangiography. The use of physiologic monitoring devices is warranted because the surgeon may not be able to visualize fine perforators through the microscope around the blades or via angiography because of their size and position deep within the operative field.

Videoangiographic fluorescence imaging does suffer from shortcomings, including false negative results. In addition, some aneurysms (for example, PCoA aneurysms) are not easily imaged since they are not visible to the camera of the microscope. Information from multiple sources should be used to confirm aneurysm obliteration.

After an aneurysm has been deemed occluded via inspection, microdoppler ultrasonography, and fluorescent imaging, I prefer to puncture it near its dome to confirm its obliteration unless a conventional intraoperative catheter angiogram unequivocally confirms its exclusion. The puncture hole is placed high in the aneurysm dome, providing aneurysm tissue for additional clipping if persistent filling is noted.

The deflated aneurysm will allow a complete inspection of the field and thorough evaluation of the adjacent branching and perforating vessels. The clip should not distort the optic nerve or be at risk of slippage upon the release of brain retraction. Overall, I have a low threshold for obtaining an intraoperative catheter angiogram to reliably confirm aneurysm obliteration and vascular patency. Retrograde versus anterograde flow within the vessels should be distinguished and corrected through clip repositioning.

If a perforating branch is found compromised on inspection, the clip must be repositioned. Typically, the clip is moved repeatedly distal on the aneurysm neck or dome until the perforator is no longer ensnared by the clip blades. If the aneurysm neck becomes too wide for the original clip, additional clipping strategies may be required to ensure its adequate closure. I bathe the perforating vessels in papaverine-soaked Gelfoam pledgets to relieve their spasm.

Persistent Aneurysm Filling

Some aneurysms may, frustratingly, continue to fill after the initial clip application. The causes are numerous, but thoughtful analysis of the reasons for each situation is warranted. Indiscriminate manipulation of the clip can lead to more undesirable consequences, such as a tear at the neck or avulsion injury to the perforating vessels due to limited maneuvering space left around the neck after indiscriminate placement of multiple clips.

I first check to see if there is a proximal or distal patency of the neck at the ends of the blades. Next, I confirm that the blades are completely approximated. These two situations are the most common causes of persistent aneurysm sac filling. If the clip is too short, a distal lumen is likely present and should be occluded with a fenestrated clip. If a fenestrated clip was used, the proximal portion of the neck may be patent and an additional clip may be added there.

The closing force of the aneurysm clip blades is not equally distributed across the blade. The heel closest to the clip’s spring mechanism will close at a higher force than the toe. If an atheroma is present at the aneurysm neck, this may result in inadequate blade approximation and an additional tandem clip will be necessary to occlude blood flow.

Regardless of how well a clip is initially positioned on the neck, the return of circulation after removal of the temporary clip and the resultant increased intraluminal pressure may cause displacement of the permanent clip. This displacement may be acceptable or it may result in aneurysm refilling. If the clip position is no longer acceptable, the clip should not be immediately removed. Rather, I place a second clip proximal to the displaced clip, which is used as a scaffold. After successful placement of the proximal clip, the displaced distal clip is removed.

Delayed clip displacement is also possible. This can occur if only a small clip is used to ligate a broad-based PCoA aneurysm perpendicular to the ICA. An angled fenestrated clip that encircles the ICA can easily avoid this agony.

Tandem Clipping Methodology for Exclusion of a Large Partially Atherosclerotic Aneurysm with Persistent Intrasaccular Filling

Pearls and Pitfalls and Lessens Learned

The basic tenets of aneurysm dissection and clip application involve:

- Sharp arachnoid dissection and avoidance of excessive brain retraction

- Proximal control, methodical dissection along the normal vascular tree toward the aneurysm neck

- A relative liberal use of short periods of temporary occlusion provides aneurysm decompression so that I can identify and protect the neighboring perforators

- Meticulous and patient aneurysm dissection thoroughly discovers the aneurysm’s anatomy and clarifies an unhindered corridor for clip application

- Placement of the permanent clip before adequate exposure of neck pathoanatomy will lead to inadequate clip ligation, perforator injury and ultimately intraoperative aneurysm rupture

Contributor: Jonathan Weyhenmeyer, MD

References

Lawton M. Seven Aneurysms: Tenets and Techniques for Clipping. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers, 2011.

Please login to post a comment.