Arteriovenous Malformation

Overview

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are vascular lesions characterized by high-flow pathologic shunting between the arterial and venous circulations with an intervening nidus of dysplastic vascular channels but no capillary bed. AVMs vary in their degree of arterial supply, nidal size, and location, flow-related aneurysms, and venous outflow. Lesions are typically within the subpial space supplied by the cerebral arteries, although AVMs often parasitize dural branches.

Changes in the adjacent or underlying parenchyma identified on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been hypothesized to result from vascular-steal phenomenon and venous congestion. Clinical symptomology is variable and generally related to intracranial hemorrhage. AVMs are occasionally discovered incidentally. Brain AVM, pial AVM, cerebral AVM, and non-Galenic cerebral AVM (CAVM) are synonymous.

Imaging

- General features

- Subpial space nidus, distinct from dural and subarachnoid arteriovenous (AV) shunts

- Supplied predominantly by pial arteries, may parasitize dural branches

- AVMs are solitary and sporadic lesions in the vast majority of cases (98%)

- Locations: supratentorial (~85%), posterior fossa (~15%)

- Multiple AVMs are rare, usually syndromic

- Cerebral (cerebrofacial) arteriovenous metameric syndrome (CAMS)

- Segmental craniofacial AVMs, often very complex lesions

- CT

- Nonenhanced computed tomography (NECT)

- Parenchymal hematoma and/or intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) (subarachnoic hemorrhage [SAH] only occasionally to rarely)

- Isodense to hyperdense serpiginous structures representing the nidus

- Portions may be calcified

- Mass effect by AVM directly, if very large, or hematoma, if present

- Small AVMs that have not hemorrhaged are likely to be overlooked

- Status post embolization, liquid embolic agents appear very hyperdense

- If there is evidence of rupture and hemorrhage, proceed to contrast-enhanced (CE) study

- CT angiography

- Maximum-intensity projection (MIP) and 3D reformats useful in characterization

- Depicts hypertrophied arteries and draining veins

- Allows good approximation of distribution of arterial supply

- Strongly enhancing nidus

- High-flow shunts result in early draining veins and contrast-opacified dural sinuses demonstrated on arterial phase

- Limitations

- Beam-hardening artifact

- Bone (skull base and posterior fossa)

- Metallic artifact

- High attenuation of endovascular coils and liquid embolic agents can obscure residual nidus

- 3D reconstruction and surface-shading software may produce artifacts

- Limited or judicious use in patients with iodine-based allergy and/or renal dysfunction

- May require contrast dose adjustment considerations for subsequent catheter angiography

- Nonenhanced computed tomography (NECT)

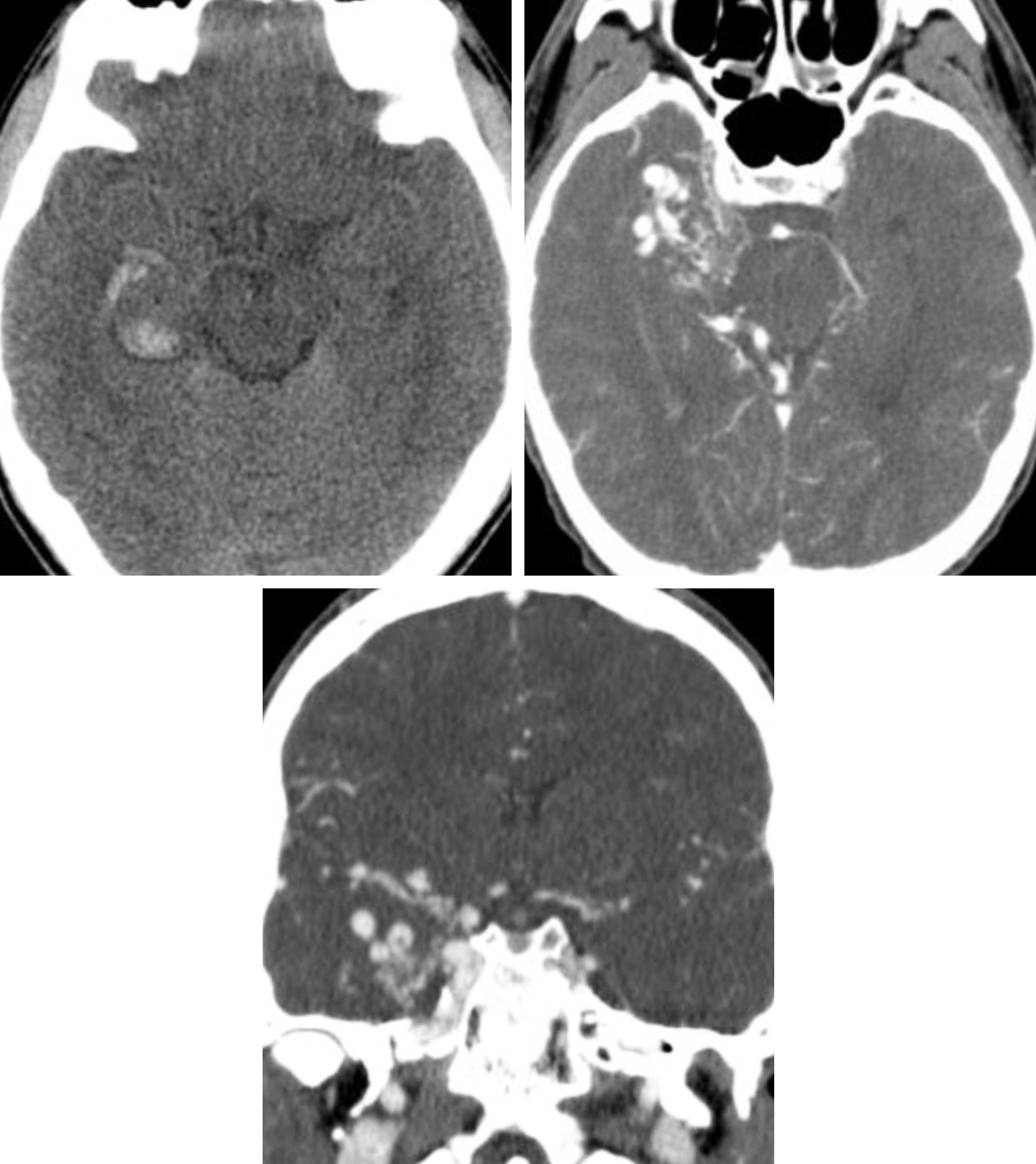

Figure 1: (Top Left) Typical NECT appearance of an AVM with relatively ill-defined isodense to hyperdense vessels replacing brain parenchyma with evidence of small adjacent parenchymal hemorrhage in the right temporal lobe. (Top Right and Bottom) CT angiography (CTA) increases the conspicuity of the underlying AVM, revealing abnormal right temporal nidiform vessels.

- MRI

- Findings

- Excellent sensitivity and specificity for detection and relative staging of blood products

- Tangle of serpiginous flow voids

- Adjacent parenchyma likely to demonstrate gliosis and/or venous congestion

- Typical pulse sequences

- T1-weighted imaging

- Signal varies with flow rate, direction, and stage of blood products from hemorrhages

- Tangle of serpiginous black flow voids representing the nidus

- T2-weighted and FLAIR imaging

- Tangle of serpiginous black flow voids representing the nidus

- Variable T2 hyperintensity and volume loss representing gliotic change in the underlying/adjacent parenchyma

- Variable T2 hyperintensity and expansion representing venous congestion edema in the adjacent parenchyma, typically in the territory of draining veins and dural sinuses

- T2* GRE and SWI

- Susceptibility artifact (blooming artifact) representing hemorrhage if present

- T1WI C+

- Enhancement of nidus

- Rapid flow may demonstrate signal loss without enhancement (vascular flow voids) on traditional spin echo T1-weighted postcontrast images

- Can greatly increase the characterization of the enhancing vessels of an AVM when inversion-recovery spoiled-gradient recalled-echo (IR-SPGR) 3D sequence is obtained

- T1-weighted imaging

- Findings

- MR angiography

- Technique

- 3D time of flight (TOF)

- Spatial resolution of modern 3D TOF MRA on the order of 1 mm3

- Axial source images

- MIP images derived from source data

- CE MRA

- Useful in surveillance, staged treatment follow-up

- 3D time of flight (TOF)

- Metal suppression techniques can be employed

- MRA should generally be considered complementary to conventional MRI

- Best to include CE-MRA as well as GRE or SWI sequences

- Feeding arteries are often easy to identify (because of location and dilatation)

- Draining veins can be identified by their larger caliber relative to arteries and drainage into deep or cortical veins

- Limitations

- Prone to multitude of artifacts that can be both helpful and difficult to interpret

- Pulsation artifacts may be seen with AVMs

- Pulsation artifacts become more pronounced on CE images

- Generally less cost-effective, less availability

- CT is performed more easily for uncooperative and/or combative patients

- MRA pitfalls

- Intrinsic T1 shortening, such as in subacute hemorrhage, may simulate vascular flow on TOF MRA

- Subtle early draining veins may be the only finding in otherwise occult, largely thrombosed AVMs

- Technique

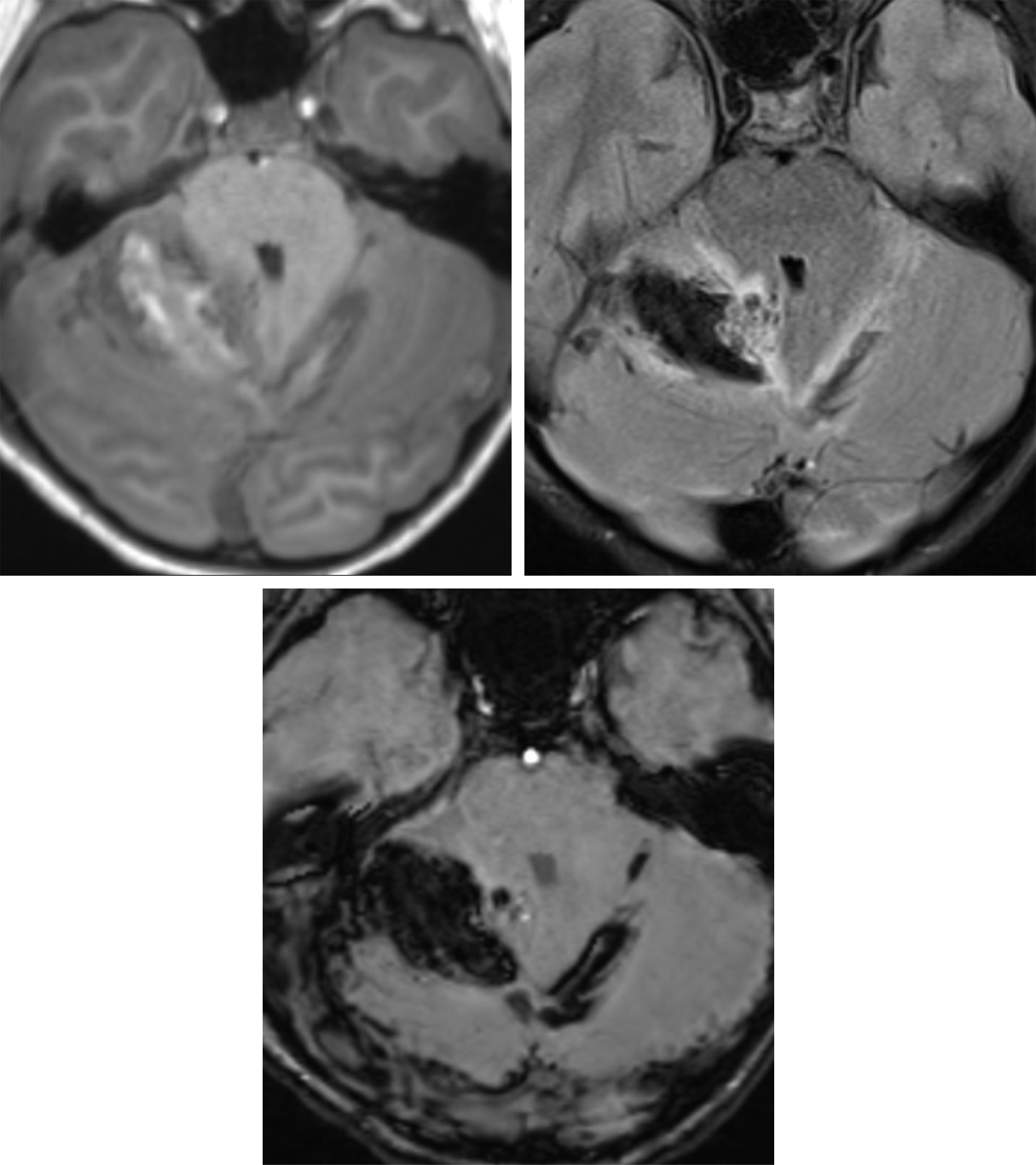

Figure 2: T1-weighted (top left), FLAIR (top right), and SWI (bottom row) axial MR images illustrate mixed-stage blood products of subacute parenchymal hematoma within the superior right cerebellar hemisphere with associated SAH within the adjacent cerebellar sulci and crossing midline. Nidiform flow voids are present at the medial aspect of the hematoma on the FLAIR image, consistent with an underlying cerebellar AVM.

Figure 3: Axial T2-weighted (top left) and T1-weighted (top middle) imaging reveal large dilated serpiginous and clustered nidiform flow voids centered on the central sulcus at the right frontoparietal junction. Axial T1-weighted C+ imaging (top right) demonstrates robust postcontrast enhancement in a pattern consistent with high-flow AVM. Sagittal T2-weighted (bottom left) and coronal T1-weighted C+ (bottom right) imaging again demonstrate the right frontoparietal AVM centered on the central sulcus involving eloquent cortex (Spetzler-Martin grade 4).

- Digital subtraction angiography

- Findings

- Best characterization and delineation of AVM angioarchitecture

- Location/depth

- Hemispheric, lobar, basal ganglial, thalamic, callosal, intraventricular, cerebellar hemispheric, cerebellar vermis, brain stem, perimesencephalic

- Nidus size and compactness

- Flow physiology

- Predominant nidal flow, or

- Fistula (shunt) predominant, or

- Mixed

- Arterial supply

- Organized by major feeding territory

- 25% to 33% may have pial and dural arterial supplies

- Associated aneurysms

- Number and location

- Nidal (>50% of cases)

- Flow related (of the feeding arteries, 10%–15% of cases)

- Proximal aneurysms at the level of the circle of Willis branch points

- Venous

- Degree of pial collaterals and Moyamoya changes

- Venous characteristics

- Early draining veins ± venous stenoses due to high-flow venopathy (may increase intracranial hemorrhage risk)

- Number of draining veins

- Superficial versus deep drainage

- Presence of venous angiopathy such as hypertrophy, outflow stenosis

- Eloquence

- Several regions of the brain defined by Spetzler and Martin that, when damaged, result in more debilitating deficits

- Staging, grading, and classification

- Spetzler-Martin scale, derived by DSA findings

- Global assessment and estimated surgical risk, from 1 to 5

- Size

- Small (<3 cm) = 1

- Medium (3–6 cm) = 2

- Large (>6 cm) = 3

- Location

- Noneloquent area = 0

- Eloquent brain = 1

- Eloquent areas: sensorimotor cortex, visual cortex, hypothalamus, thalamus, internal capsule, brain stem, cerebellar peduncles, deep nuclei

- Venous drainage

- Superficial only = 0

- Deep = 1

- Spetzler-Martin scale, derived by DSA findings

- Findings

Figure 4: A 16-year-old boy with cerebellar AVM. Axial T2-weighted (top left) and TOF MRA (top middle and top right) imaging reveals an AVM with a parenchymal nidus within the right superior cerebellum and large varix within the quadrigeminal plate cistern. DSA images obtained from arterial to venous phase at high frame (left to right) demonstrate the angioarchitecture of the superior cerebellar AVM with direct supply by the bilateral posterior cerebral artery and superior cerebral artery as well as en passant supply by the right anterior inferior cerebellar artery. There is early opacification of the internal cerebral veins, vein of Galen, and straight sinus.

Figure 5: A 6-year-old girl with seizure. Axial NECT (top left) demonstrates an ill-defined hyperdensity at the left midfrontal convexity. Postcontrast CTA axial (top middle left and top middle right) and sagittal MIP (top right) reveal an abnormal nidiform cluster of vessels and 2 dilated varices in close proximity. Precontrast coronal T2-weighted MRI (bottom left) and postcontrast T1-weighted MRI (bottom middle) place the lesion in the left prerolandic region; there is characteristic flow-related signal loss within the larger varix on T2-weighted imaging, as well as numerous dilated flow voids surrounding the nidus. (Bottom Right) Dynamic CE-MRA image demonstrates the spatial relationships of the left prerolandic AVM and varices; enlarged cortical veins are identified emerging superiorly toward the superior sagittal sinus and inferolaterally toward the superficial sylvian territory and vein of Labbé.

Figure 6: Imaging of the same 6-year-old girl with seizure shown in Figure 5. Left internal carotid arteriography (top left) and left anterior oblique (top right) stereoscopic images (stereo image pair obtained at slightly different projection angles, viewed by crossing eyes) and lateral projection image (bottom left) illustrate the complexity of the left prerolandic AVM with direct supply from the prefrontal division of the left middle cerebral artery and en passant supply from the precentral division and venous drainage via 2 main conduits, each associated with dilated venous varix. (Bottom Right) Left internal carotid arteriography lateral projection status post endovascular embolization (Onyx) and surgical resection demonstrates no residual arteriovenous shunting or nidiform vessels.

For more information, please see the corresponding chapter in Radiopaedia and the Arteriovenous Malformation chapter within the Brain Tumor Mimics subvolume of The Neurosurgical Atlas.

Contributor: Daniel Murph, MD

References

Shapiro M. Neuroangio. 2016. http://neuroangio.org.

Santos ML, Demartini Júnior Z, Matos LA, et al. Angioarchitecture and clinical presentation of brain arteriovenous malformations. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2009;67:316–321. doi.org/10.1590/s0004-282x2009000200031

Maruyama K, Koga T, Shin M, et al. Optimal timing for Gamma Knife surgery after hemorrhage from brain arteriovenous malformations. J Neurosurg 2008;109(suppl):73–76. doi.org/10.3171/JNS/2008/109/12/S12

Kim H, Pourmohamad T, Westbroek EM, et al. Evaluating performance of the Spetzler-Martin supplemented model in selecting brain arteriovenous malformation patients for surgery. Stroke 2012;43:2497–2499. doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.661942

Lawton, MT. Seven AVMs: Tenets and Techniques for Resection. Thieme Medical Publishers;2014.

Spetzler RF. Comprehensive Management of Arteriovenous Malformations of the Brain and Spine. Cambridge University Press;2015. doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139523943

Please login to post a comment.